During this unsettling time when we are advised to self-isolate because of coronavirus, many dog training professionals are exploring ways to continue business as usual in an effort to serve their clients and to maintain income. Taking your training classes online is one way to achieve this.

While the current priority is to fill in a gap until work life returns to normal, think of this as an opportunity to develop new lines of business and materials that will support your work well into the future.

This resource is intended as a sweep through a few key considerations as you design and implement your first online course. The goal is to get you up and running quickly. Down the road, you may wish to invest more energy into developing a robust online learning component of your business. For now, let’s just get started!

Initial Steps

“Wolf” by Sheep’R’Us is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

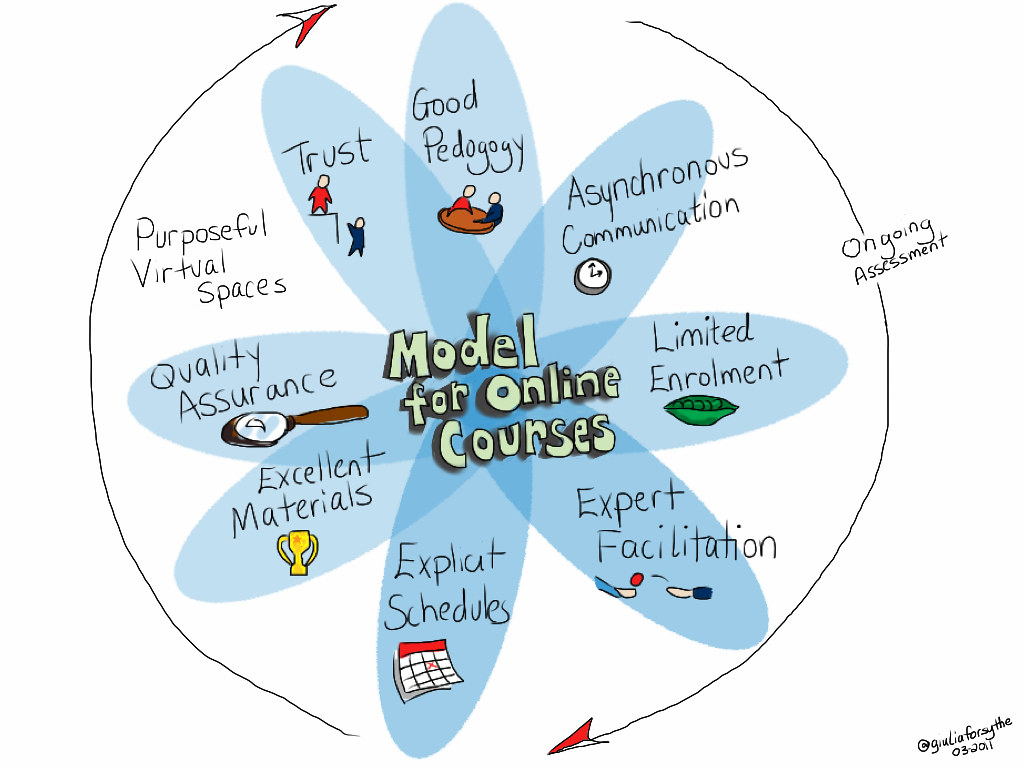

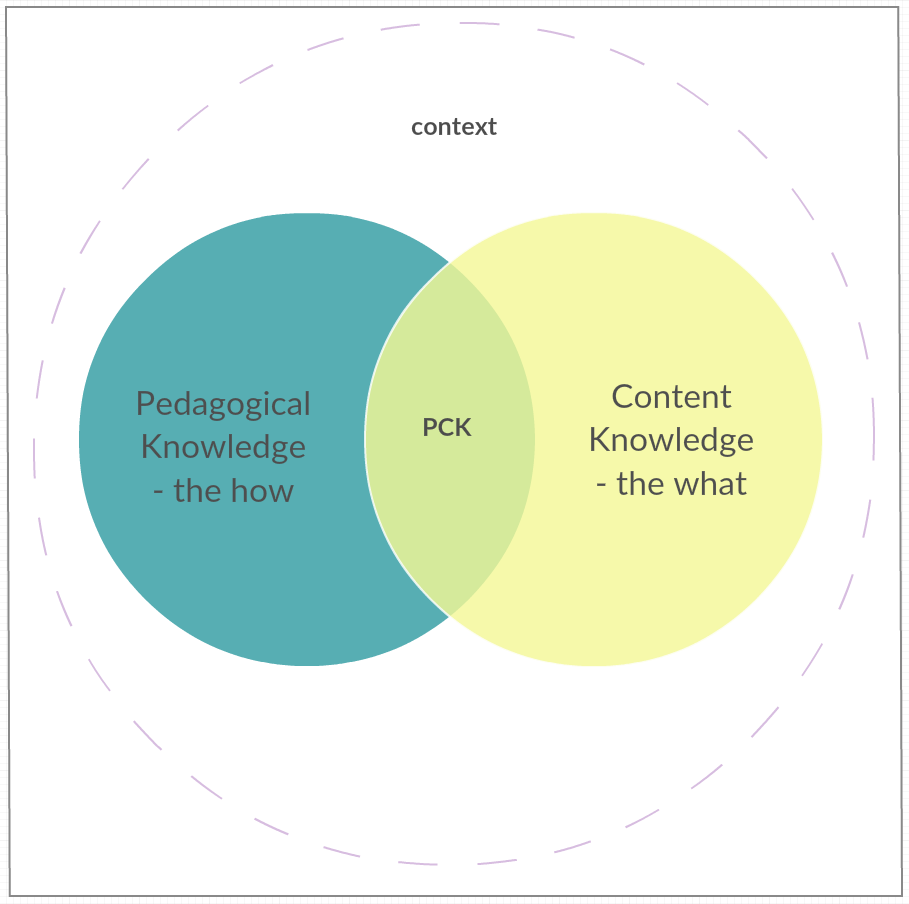

There are endless configurations for how you might go about implementing your course. First and foremost, the models and strategies you choose should be driven by the needs of the learners and the nature of the topics and objectives. It can be tempting to tell your students everything you know, but deeper learning happens when they are actively engaged in the learning process.

Dog training classes would typically use one or all of these three instructional models:

Direct

Is the focus on developing skills? Are you providing step-by-step instructions to achieve a specific outcome? Then you are probably going to lean toward direct instruction.

Examples of methods in this category include teacher-led presentations, written instructions, and demonstrations.

Indirect

Is the focus on exploring concepts and encouraging critical thinking? Then more indirect approaches can help your students to make connections and problem-solve.

Examples of indirect activities are quizzes, matching exercises, analysis of content (videos, documents, etc), and creation of training plans.

Experiential

Will your students benefit from doing different exercises, and reflecting on their own performance and progress? Experiential learning is a process of developing knowledge and skills through direct experience. No doubt all dog training classes aim to achieve this. However, true experiential learning takes the doing a step further; as instructors we need to foster ways for learners to identify needed changes in their own skills and understanding.

Experiential learning activities includes anything learner driven and hands-on. For example, following a demonstration of training a dog a new behaviour, you might ask your students to create a video of themselves following the same steps. This can be followed by self-reflection and peer or instructor feedback.

Before we move on

There are additional instructional models that focus on independent study and collaboration. As there is considerable overlap with the three listed above, they are not elaborated on here.

Creating your design and content

Keep it simple

Online course design work is never finished. You will always be improving the materials and format of your course. In light of that, do what you can now so you can move more quickly to continuing your dog training services.

In the early days of online teaching the focus was on organization and structure because there simply weren’t a lot of tools available. Nowadays, there is no shortage of ideas and tools! It is easy to be attracted to the bells and whistles and lose sight of our original instructional goals and learning outcomes. Stick to tools that are familiar to you or easy and quick to learn, and if a tool doesn’t fit your goals, put it aside.

Be mindful of the amount of time you spend on making your content look polished. For example, when creating PowerPoint slides or websites, it’s easy to spend more time selecting a colour scheme and layout than it is actually creating meaningful content.

Be inclusive

Use tools that your clients will likely be able to use easily.

While platforms like Facebook may offer quick and easy solutions for you, keep in mind that not all clients are also familiar with, or interested in using, this platform. If step one is to ask a client to create a Facebook account, then abandon that choice. It is simply too much to ask.

Don’t underestimate the benefits of simple email communication! It is accessible and, used well, it can be very effective.

Many free content hosting, learning management, and communication platforms provide exactly what you need to ensure everyone can participate. See the resource section below for links to these tools.

Remember online is different

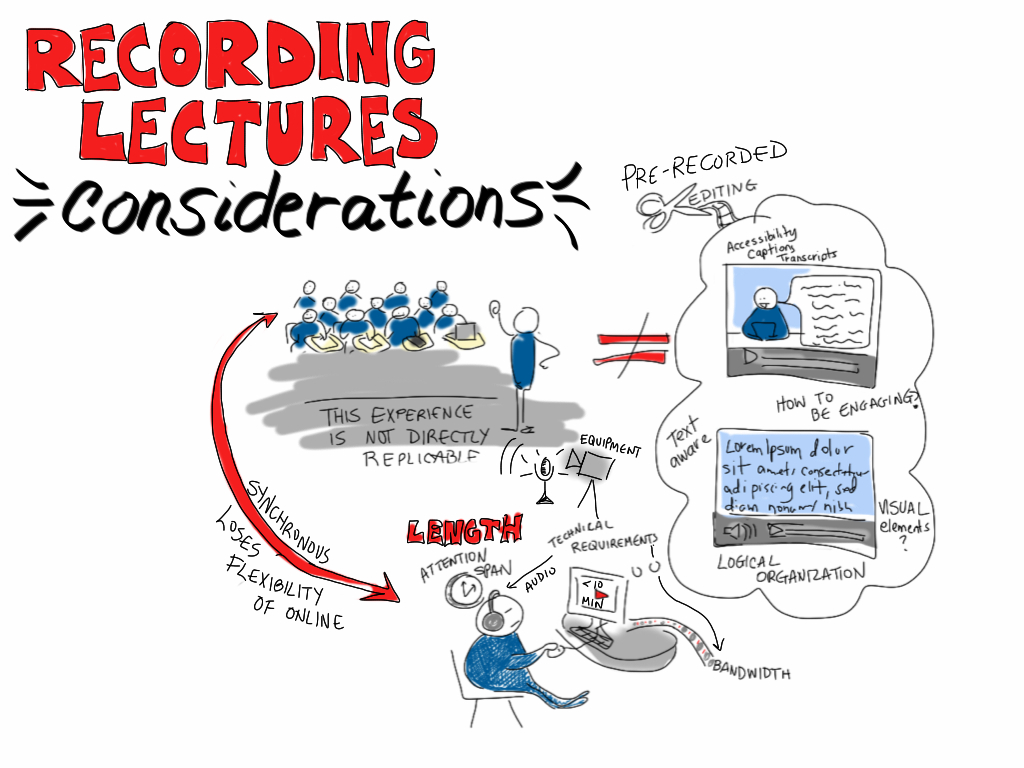

It is impossible to replicate the classroom experience. This means you need to rethink design and format, and sort through different scenarios of how you will accomplish your course goals.

For example, in the classroom you may be able to speak passionately about your dog training experiences and hold attention for a long period of time, but keep in mind that in that venue you are communicating with more than your voice and can also receive clear signals from your learners about their level of interest.

You will also need to consider that communication is not always immediate. This is not necessarily a bad thing! It allows more time for thoughtful and organized questions and responses.

Provide easy access to content

Avoid sending content as email attachments. Hosted content respects the individuals on the receiving end who might have challenges downloading and viewing materials sent through email. There are many free online services that store your content: Google Docs, YouTube, Dropbox, WordPress, Wix, to name a few.

Even with hosted content you need to consider the format and file size of any materials you intend for clients for download. Most students will be able to read on the web or download a PDF. Other less common file formats should be reconsidered. Ideally, your hosted materials have options for both viewing online AND downloading.

Organize your content using standardized headings, file names, and structures. Avoid publishing the same information in a different places. This what the Web is designed for – linking! This consistency and streamlining will make it easier for students to find and revisit content.

Keep the course manageable

Determine how much of your interactions with your students need to be scheduled (real time) and what can be done through asynchronous (anytime) communication. You may be surprised at how little really needs to be scheduled.

Chunk your content into small, manageable pieces, and keep it on topic. For example, a 3-minute instructional video is more likely to be watched to the end than an 20-minute video.

Consider the learning curve for your students. It takes time to learn and navigate a new learning environment, and to create their own content such as videos of their training sessions.

Delivery

Create a rhythm and flow

Plan activities and your communication around a schedule. For example, consider a Sunday “Get ready for…” sneak preview of the week, or a short weekly recap video. Use your imagination and keep it the same each week. The more we build anticipation in our courses the stronger the engagement.

Communicate clearly

It takes time to craft your communication so that it is clear and concise. Students may not realize the effort you take, but they sure will appreciate it. Some quick tips:

- Use headings to chunk the information

- If you mention a resource available on the Web, LINK to it rather than explain how to find it. (Starting out you might include navigation tips, but fade these out over time for the sake of brevity.)

- Keep your writing crisp and concise

- Use bullet points instead of long paragraphs

- Use visuals to convey information quickly

- Any important details that students might need to revisit, such as due dates, should be in written text (not video!)

Manage time well

While there is a place for one-to-one communication with individual students, this is simply not scalable in an online course. You will soon run out of time if you try to respond to questions and provide feedback to each student. Instead, consider that all students will benefit from hearing the questions and answers that emerge throughout the course.

Publish a frequently asked questions (FAQ) page that you can add to over time and re-use in future courses.

Build a database of “canned” responses over time to avoid re-writing the same information.

Depending on your strengths and skills, it can be less time-consuming to create short videos than to write everything out (However, consider your students’ time as well.)

Make good use of any scheduled time with your students. If you plan to lecture, consider recording that and instead use “real time” for discussions and other activities.

Always create content with the idea it can be reused in future courses.

Be yourself!

Just as with in-person classes, the more you appear relaxed, use humour, and admit to your shortcomings, the more likely your students will feel comfortable in their participation.

Having said that, it’s possible to inject too much of yourself into the course. For example, turning the camera on yourself is a great way to be present and establish a connection with your learners. However, there is no need for your learners to watch you during an entire lecture. Give them speaking points and visuals instead!

Final comments

As mentioned, this resource only touches on some of the key considerations for designing and implementing your first online course. There’s much more to the process and it takes time and effort to create really effective learning experiences. You don’t need to do everything all at once! And remember, some of the most successful courses use very basic tools and simple designs.

Resources

As I was busy assembling a list of free, cloud-based tools to support dog trainers who would like to move their classes online, I came across this amazing crowd-sourced resource launched by Stephen Downes. Following my own advice not to duplicate information, I’ll consider merging my findings with this list!

Creating an Online Community, Class or Conference – Quick Tech Guide

Videos

Videos YouTube also has a

YouTube also has a